Watch the video on YouTube

Data Types

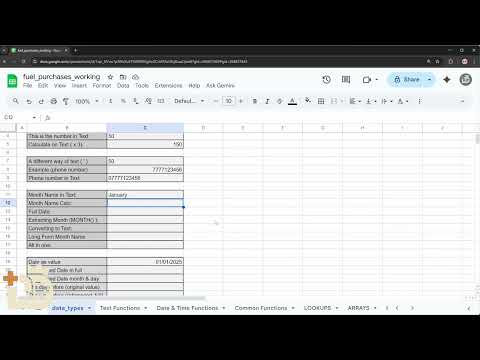

In this lesson, we take a brief look at the two primitive data types in Spreadsheets: Numbers and Text

Quick note:

I’m still contstructing the sheet you see in this and future videos, and I’ll share it when I’ve figured out the best and most secure way to do so.

Intro

Hey, welcome back everyone. It’s good to see you!

So one of the major principal things that - I know it took me a while to get my head around when I was first working with data - is the idea of a data type. Now, when you work with like really complex systems, but there are many, many different data types. But in spreadsheets, there’s actually only really two primitive types. I mean, you know, don’t at me if you know there’s actually a little bit more than that, but we’re going to actually just base on the direction being two primitive types. And those two primitive types are actually numbers and text. It actually just doesn’t get any more complex than that. All that does change within the spreadsheet is actually not only whether it’s a number or whether it’s a text, it’s actually just how it shows. So this is going to be the first video where I’m really sort of playing about with numbers. I’m going to have a look at a little bit of text as well, but on the basis actually of… dates as well because a date is actually as we’ll come to see a number type also.

So we’re going to start off with this. So I’ve got this sort of spreadsheet here. I will be sharing the spreadsheet by the way. I’m still trying to figure out the best and most secure way of actually doing that. But so keep an eye out because once I’ve got it all finished, as you can see at the bottom there’s quite a few tabs there once I’ve got it all finished I’ll figure out and allow the blog post have a look at the website https://datawithduke.com to figure out how to get it.

Basic Arithmetic.. on Text?

So Let’s start with this. We’ve got a number. We’ll start with 50. This is good as any, right? But we’ll just start with that. We can run calculations. We could do basic arithmetic basically on any number by referring to the cell itself. So if I start off with an equal sign and I’m going to click on this cell here, which is C2, and that represents the number 50. And you can see that in the top there. It says 50 is the value that is being referred to by looking looking at cell C2. And then if I do the multiplication symbol, which is an asterisk, and that’s pretty common in pretty much every single data tool, certainly that I’ve ever worked with. So I do that, and I do 3, and I hit enter, and there we go, there’s result. Fantastic.

So basic calculation, I’ve got a number 50 in a cell, and I’m going to refer to that cell, I’m going to multiply by 3, and it gives me the response nice and easy.

I mentioned that there’s actually two primitive data types being numbers and text. We can convert back and forth to each other as well. And there’s a couple of different ways of doing it. But the first way that I’m going to show you is with the text function. So I’m going to name text. That’s the function itself. I press the equal sign and I’ll type the word text. And you see this little green box that appears to say, oh, you’re trying to do a function. Let me help you. which is actually quite useful. Now it asks for a number, but I’m going to refer to the number that sits in cell C2 again. So that’s what I’m doing. And then I put in a comma and it highlights, well, what format do we want? So we can specify any sort of format or whatever, but I’m just going to put in a zero for now to specify that I want it in like a numerical sort of format. I close off the brackets just to close off the function. And there we go. That’s the number itself in text.

Alignment matters

Now you’ll notice that it’s actually aligned over to the left. And this is something that’s pretty useful to know is that in spreadsheets, generally speaking, numbers… automatically align to the right and text will automatically align to the left. Now you can change it, that’s a future video, but you can change it around. But it’s a good thing to know. If you’re just playing about, before you start playing about with alignment and things like that, if it’s aligned to the left, it’s probably text. If it’s aligned to the right, then it’s probably numbers.

So what we’ve actually got here is the number 5 and 0 in text. That’s what’s actually been returned here by converting it to a text type. Then surely I can’t actually do mathematics on text, right? But let’s do that again. Let’s multiply that value in C4 this time with 3. But it’s still returning a number. even though it’s text. And that’s because the system, the spreadsheet is actually clever enough to know is that even though it’s text, the data type itself is actually text. But that it knows that the text itself is made up of just numbers. So if I try to perform some arithmetic on it, it converts it back into a number for me just for the purpose of the calculation. So we’ll be coming on to why that’s important again on future videos, but because some things will work with text and some things will not work with text. But that’s sort of good to know that if we have text, whether it’s a number or not, if it’s only just actually made up of numbers, like in this case, then you’ll still be able to run arithmetic calculations on it. So that’s the text function. That’s how that works.

Alternate way to convert to text

There is actually another way to denote text as well, but just put an apostrophe in before you put numbers. So if I were to represent the number 50 again in text data type, I put in an apostrophe, type in the number 50, and there we go. Now, the apostrophe disappears because that’s literally just a function to say whatever comes after this apostrophe, this singular apostrophe, I want you to display as text. And that’s where it’s done that. It’s returned the number 50, but it’s aligned it over to the left. We know that it’s text.

Numbers as text… why?

And you might be sitting there thinking, well, okay, well, why would we want to do that? And the reality is that all over the world, there’s actually lots of reasons why a numerically formatted data point might actually need to be displayed as text. And let’s think about phone numbers. Let’s just say that my phone number is 07777123456. If I was just to put that in as a phone number, let’s just say that I’m creating a spreadsheet and I’m storing like contact details of people and this is somebody’s phone number. I hit enter and it aligned over to the right and it drops the preceding zero because it doesn’t realize that this is a phone number that I’ve actually typed in. It thinks that I’ve actually typed in a number. and that’s what’s going to be 7,777,123,456. That’s actually what it thinks it’s seeing here.

But no, wait a minute, I want a phone number. So if I proceed it with a zero, type in the same thing again. There we go. This time it’s aligned over to the left-hand side. It’s kept a preceding zero. The number itself is text, and that’s a phone number. That’s something that we can use. So that’s pretty cool. So far, there’s a couple of other reasons like, you know, zip codes in America. And I believe actually zip codes in lots of countries of the world, actually, are five or four or five digit characters. And some of them have preceding zeros. So there’s a couple of use cases, legitimate use cases out there where we might have to put a number actually as text.

Check out my other pages

Anyway, let’s come back on to dates. Now, I am going to do a full video when it comes to date functions, because if you’ve been watching the short videos on Facebook and Instagram, but you’ll see that we’re actually using elements of dates in order to run some quite complex calculations. So go and check those out. If you haven’t seen them, go and look me up, [https://facebook.com/datawithduke](Data with Duke on Facebook), https://www.instagram.com/datawithduke/. You’ll also find me on https://www.linkedin.com/groups/14943110/ as well if that’s your thing. And what I’m doing there is just a series of short videos where we’re actually doing some very basic analytics. And as part of that, we’ve been looking at actually breaking down months into component parts.

Playing with dates

So above what we did is that we took a text and we were able to run calculation on it. So if we have text of January, then surely we can probably actually just grab the month element of that and run calculations on that as well. Right? So let’s try that. We’ll do month and C11. That’s where the cell is. And I hit enter, but I’m getting an error. We actually get an error here. If I hover over this error, it actually gives me some really useful feedback. And it says that in the month function parameter one, I’ll be going through that in a bit more detail later. But let’s just say whatever we put into the brackets of that month function expects number values. But January is text and it cannot be coerced to a number. We cannot change January to a number in any specific way unless we sort of tell it how to do that.

So how do we play about with dates with text and moving back involved in numbers and text? So we’ll start off with a basic date. 1st January 2025, good as any. Notice that when I type it in, it aligned right like other numbers, and that’s because dates are… actually just numbers, just have a different sort of format, a different display. So I’ll be going into that in a second. So if I want to extract the month now of that date to say that actually C13 is what I’m looking for, and I hit enter, there we go, number one. It’s telling me that month one is what we’re looking at. All right, fantastic. Month one being, of course, in most places, is going to be January. Great, we might be able to use this.

Converting Dates to Text

But the number one isn’t always actually useful without context. So maybe we actually want to take the month of it and then actually convert it into text like we’ve done the number above. So again, there’s a couple of different ways of doing this. I’m going to go through a few. So we’re going to use this text function again. The number this time that I’m asking for is actually the date. I’m going to be… The text function says, well, what’s the number? And I’m pointing it out at dates. And this is what it says. No, I don’t get it. I don’t get it, Duke. Dates are just numbers with a special format. So keep following, keep watching. And we’ll see what we mean by that. So I’ve got the number, which is actually represented by a date. And then inside… Double quotes. I’m going to say a format that I want the date, that number, to actually come in. Now, again, I’ll be doing a future video on date and time functions a little bit more detail, but let’s just take it for now. If I was to type in three M’s and then close off the brackets, what I’m actually asking for, MMM, is a short named month of that particular date. So what it’s doing is that it’s going to that date first of January 2025 and it says look at the month and return, look at the month of that date and then return a short form, a short form word to represent that month. So January is shortened to Jan, just three letters. If I wanted the full, I could actually do the same thing again. So I can point it to the number, but in this case it’s actually a date. And in my double quotes, this time I’ll go “mmmm”.

Now this isn’t another snack coming for us. We’re actually saying this time, using four M’s, I want the long form version of the month in cell C13. So here it’s entered there and it’s done the same thing, but this time it’s saying January, not just Jan. So that’s kind of useful. You can actually go into a lot of detail and again, I’m sounding like a stuck record, but there is going to be a future video going into this in a lot more detail. But let’s just say that I want to grab different elements of that date. So I could do the same thing. Let’s go text. My number is going to be C13, which I’ve typed in this time rather than click on it. And then inside my double quotes this time, I’m going to say D just for one day. I want the singular version of the day if you can. We’ll have the full month, mmmm. And then I’ll do YY to say that I want the year returned in a two-digit format. And then I’ll close off the brackets there. And there we go. 1 January 25. And that’s just through the text format, just through the text function. I’ve taken the date there, so make it look nice and pretty.

Dates in different formats

Okay, so the problem with that is that because we’re converting it to a text, sometimes we can run arithmetic calculations on it and sometimes we cannot. So there’s an alternative way that we can have a look at this and we can actually change the format of what we’re seeing on the screen itself. So we’re going to start again with the same date, this time 1st of January 2025. And what I’ll do is I’m going to reference it. C19 is what we’re heading for. So it returns the same thing. But this time, it’s actually returned the date in full, Wednesday, 1st, January 2025. You’re like, well, wait a minute, how did you do that? Well, that’s because before I recorded this video, I actually went in and edited the format of each of these cells. Okay. I’m sure you have to do that in the menu at the top. You’ve got a button that says format, a menu that says format. And I’m going to go to number. Remember, a date is just a number in a slightly different format. And how do I know this? Well, actually, we’ve got date here as an option. a little bit further down. If I scroll right down to the bottom to say that I want custom date and time, it’s a date and time that I’m specifically looking for, I click on that and what it’s telling me here is this is how my date is gonna be formatted.

It gives me the day and it gives me an example here. This isn’t the actual day that I’m looking at in the cell, but it’s an example Tuesday. But then the actual day as a number, so the fifth, a comma separating the two, I suppose. We have month, which is August, and we have a year, as an example, at 1930. Now, you can actually adjust all of these as time goes on, and we’re going to have to play about with all of those, but that’s actually just a common way. We’ve got the full date that way. If I were to actually just have the month and day, well, again, I could do the same thing. Let me reference C19. And this time what it’s done is that we’ve referenced the date above just the month and the day. Let’s have a look at the format this time. Let me go over to number. Go to custom date and time. And this time all I’ve done is that I’ve said that it’s the month that I’m looking at. The month is full name is what I want. Give me the example August. And then I put the little and symbol, the ampersand sign in between there. And then this time I’ve actually said, well, give me the day. Either with or without the leading zero. I think I’ve chosen without the leading zero here. So if it’s a single character, it just shows us a single character. Instead of zero, five, it just shows five.

Dates Are Just Numbers

So you can actually play about with the formats as much as you like, but underlying this is still the numerical value. So if I wanted to run calculations on that, I can still do that. So what do you mean run calculations on dates, Duke? What are you talking about? So if I reference C19 again and I subtract one from it, Well, what does that mean? And you can see it’s already appearing there. If I return that, that’s the 31st of December 2024. That is one day, a single day before the 1st of January 2025. Dates are always returned as numbers. They are acting like numbers. So a single day in the calendar is represented by a single unit, a single, just a number one. If I was to subtract one from a date, it’s basically saying, what’s the day before? That’s what it’s looking at. So that’s pretty cool. We can run calculations on dates. So maybe we could run just simple arithmetic on a date, and we could find out, well, what’s the difference between this date and this state? Or how many days have I got to go until I’ve reached this particular date in the future? Just by doing simple arithmetic.

That’s pretty cool. So not only that, but you can also choose the format that you want. And once you’ve actually set a format, it gets even better. The format when you reference it actually gets remembered. So this time I’m going to reference the date in full, Wednesday, 1st of January 2025. So I’m going to look at that date, C20, but I’m going to subtract one from that. C20, let’s try that again, C20, I’m going to subtract one from that. And it’s going to give me the day before, but in the same format that is in the cell that I referenced. So cell C20 has the full date that I’ve looked at, and it’s returned that same format, but for the day before, because I’ve subtracted one to it. I could do the same again if I have a look at my method where I’ve got just month and day with a little ampersand, but I want to subtract the date from that. So this time I could do C21, subtracted by 1, and there we go. It’s taking December and the number 31 using the same format of just month and day from the cell above as well. Dates are numbers and numbers are dates. That’s just the way that they work.

No, really! Dates are just numbers!

And if you’re still not convinced, let me actually just show you this. I’m going to show you the date itself as a number. So I go with C19. C19, which is our original date, 1st of January 2025. And if I hit enter, what we’ve actually got here is the number, the date, sorry, represented as a number. Look, let me convert it. There’s the date, 1st of January 2025. But if I actually go to number and I say, I want you to return it as an actual number, it’s coming up with 45,658 with two decimal places, both being zero. Right. The date is actually represented a number. 1st of January 2025 is represented as 45,658. And I wonder where that comes from. So let’s have a look at number one. If I just put in number one right now, I’ve done a spoiler alert there. We’ll come on to that. If I put the number one, that’s the number one that I’m looking for. If I want to reference that one, that single number one, and format it as a date this time, there we go. 31st of December 1899. So if 1st of January 2025 is the number 45,658, then the 31st of December 1899 is 1. Give you just a second to think about that. Now there’s actually a little bit of trivia about this, and I’m going to share on a future video. But if you were to do exactly the same thing in Microsoft Excel, so I’m using Google Sheets as you can see, if you were to do the same thing in Microsoft Excel, you’d actually get a different value. I’m going to give 10 points to anybody in my comments who can tell me why the value is different in Excel. It’s actually quite a funny story. But yeah, like I said, I’ll tell you on a future video when we have a look at date and time functions.

Formatting numbers

But just to finish off for today, we’re looking still at numbers. We’re looking at data types as a number itself. So… Just a handy little function for you to be aware of. What I’ve got in this cell currently is a pi, which is that irrational number, the one that just doesn’t listen. It keeps going on and on and on and on and on and on and on. But I’ve only just actually got it stored to 10 decimal points. You can go and look this up. The value I’ve got here is a pi, the value of pi to 10 decimal points. There’s 10 values there. So what if I wanted to actually have that, but only to two decimal points? Well, let me refer to it again. C29 is what I’m looking for this time. You’ll see that it’s only actually returned two decimal points. Well, why is that? And again, that’s before I came in. I actually use these buttons at the top that allow you to actually change the number of decimal points that we’ve got. So if I reduce this down to two, what we’ve got here is a value of 3.14. That’s… Pi to two decimal places.

I mean, I don’t know if you did this in school, but if we ever used Pi on any of those calculations, trying to work out the volume of a cylinder or some such thing that we swore that we would never have to do ever in our lives and always complained about why we had to do it in the first place, we would usually only use Pi up to two or three decimal points. So why display all the rest if we don’t need them? We can use these buttons to actually display as many as we want to…

There’s another way of doing this um but we always urge caution with this we can actually Round it using the round function um so it’s with the round function it says well well what what do you actually want around what’s the value you want around and i’m going to click into C29 here that’s the value that we want around and if I was to say that I actually want it rounded to two decimal places then it will return 3.14 for me And on the surface, this looks the same as this one, where I’ve formatted it to two decimal points. But it’s not. And let me prove it to you.

Rounding should be used with caution

I’m going to run some basic arithmetic. I’m going to take this original pi value, and I’m going to divide it by 3. And it results in 1.04719 and some bits. If I was going to do the same calculation on the 3.14 that’s been formatted to two decimal places, divide that by 3, we get exactly the same value, exactly the same value, all the way down to the last decimal point. But if I was to run that same calculation of the rounded version, divide that by 3, we actually get a different number, 1.04 and 6 recurring. And the fact that it’s 6 recurring tells us that we’re actually looking at a number with a smaller precision anyway. What we’re actually working out with these top two calculations is a division of three by this full number with all of the decimal places, whether you can see them or not. Whereas this one, 1.0466666666 as it goes on, is actually a result of the division of the rounded version. So please be careful, folks, when you’re working with numbers, you may not want to see all of the decimal places. You can actually format it so that you don’t see all of those decimal places. But if they form part of a more complex calculation later on down the line, probably shouldn’t round it unless you absolutely have to.

Of course, if you’re working with money and if you’re working with things that actually have to be fixed to two decimal places, this is where the round function can actually come in quite handy and quite useful. But it’s one that should always be used with caution, folks. On a future video, we will be going through some other common functions, including the round function and what are sometimes known as scalar functions in other sort of tools like SQL or something similar to that.

Outro

But that’s it for now, folks. Let us know what you thought. This is just the basic sort of introduction to data types. And let me just remind you, let me just say again, that on more complex data tools, there are actually many, many different types of data types. But on a spreadsheet, it keeps things nice and simple. The two primitive, the two basic data types that exist, simply numbers and text, and all that matters is actually how they’re formatted and how they appear. Let us know what you think. Go and check out my website, https://datawithduke.com. Go and have a look on our Facebook site so you can see how this is all building up towards a short form video series on analyzing fuel data sets. And I hope to see you again on the next video where we’re going to be playing about with text instead. Folks, it’s been a pleasure. This is Duke signing off.